About Me

I'm apostdoctoral researcher at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), working on a broad range of topics in robotics and control, including optimization, planning and building agile robots. I'm currently in the Learning Algorithms and Systems Laboratory, working with Prof. Aude Billard. I got my PhD from the same institute but in the BioRobotics Laboratory, advised by Prof. Auke Ijspeert. Please find more information in my CV.

Theory

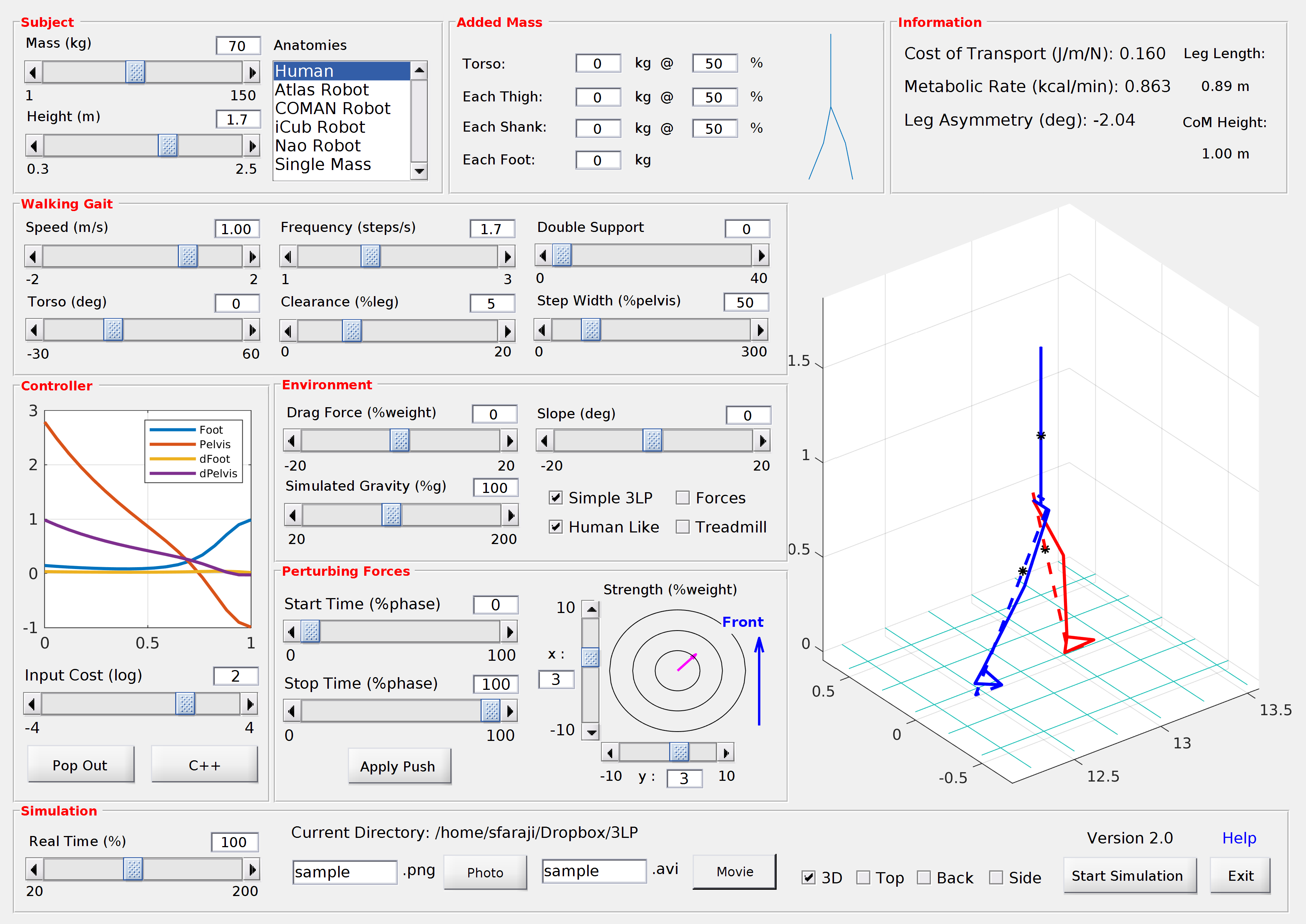

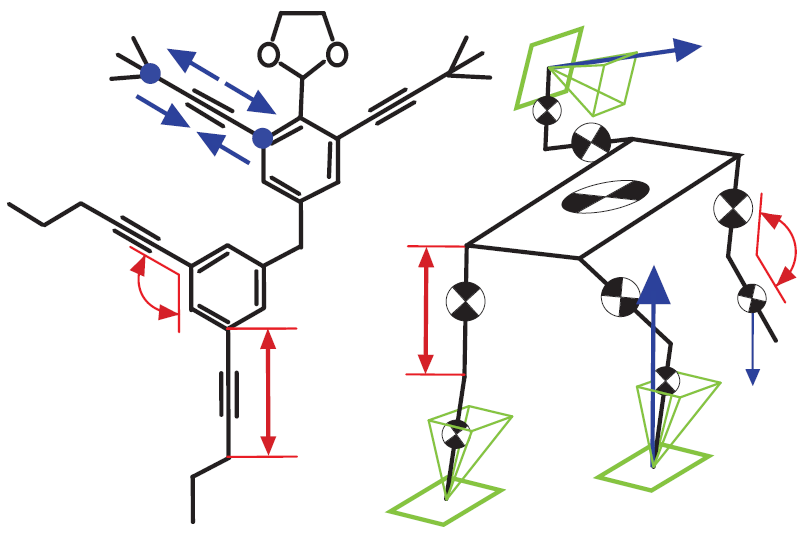

My PhD thesis focused on bipedal walking control, whole-body algorithms for humanoids and studies in biomechanics, investigating how robotic gaits are related to human gaits.

Hardware

I love building agile robots, and I actively explore state-of-the-art actuator technologies.

0 Finished Projects